The Ickleford Art Industries

I have to admit that I had never heard of the Ickleford Art Industries until a few months ago when I stumbled across some further reviews of the Home Arts and Industries Association exhibitions in the early 1900s.

For many years a thriving metalworking class and village industry existed in the small village of Ickleford in Hertfordshire. The metalworking was only small part of a number of initiatives set up by a husband and wife team with a background in the Arts and Handicrafts. In this instance a quick search revealed that the Ickleford Industries are well remembered and quite a bit of information is readily available. In this article I will try to pull together a few threads and tell the story of the metalworking class and their involvement with the Home Arts and Industries Association and the broader Arts and Crafts Movement.

An article in the Bedfordshire Times and Independent gives us a great potted history of the Ickleford classes up until the summer of 1910:

“Just beyond the frontier of this county lies the pretty village of Ickleford, which is only half a mile off the main road from Bedford to Hitchin. It is just the typical quaint old English village with its manor-house, farmyards and rustic cottages with a strange dip in the ridge of the roof, and their smiling gardens in front, assembled around several pieces of village green, which are shaded by elms and chestnuts. The Old George and the Green Man stand cheek by jowl near a venerable little church which is attributed the Normans, but seems to illustrate every period since. The village and its surroundings are quite agricultural and pastoral in character but beyond the railway arch the dwellings are less picturesque, and there are indications that the parish is not without its poor people. But Ickleford lies within the sphere of social experiment. It is not far from the Garden City, and though there may be no actual connection in the nature of cause and effect, it seems not very surprising that prophets of the social redemption should rise up in that country. At this time of year our villages appear charming places to live in, but the problem is how to persuade people to live in them all year round. There was a time, we are told, when the home arts and local industries sufficed to maintain a happy and contented peasantry, but the era of manufactures has changed all of that.

Reformers who desire to set up village industries will look with interest upon a remarkable experiment which has achieved a goodly measure of success at Ickleford. We confess that until a few days ago we had never heard of it, and hardly knew the difference between Ickleford and Ickwell Green, but on receiving an intimation that there was an exhibition illustrative of a village industry to be seen in that village, our representative journeyed over there at the first opportunity. Set amidst the luxuriant gardens near the residence of Mr. and Mrs. Walter Witter stands an unpretentious building which, from its style and flower-decked windows, obviously differed in character from the neighbouring dwellings and could not be the School which we had already passed. Venturing to enter, we at once discovered a room full of beautiful objects, and were courteously received by Mrs. Witter and her sister. In a brief conversation we learnt for the first time the nature of the exhibition.

It seems that ten years ago Mr. and Mrs. Witter came to reside at Ickleford. Mr. Witter is an artist by profession, and Mrs. Witter is the niece of Mr. John Carr, who originated at the Bedford Park estate, which was the first attempt to provide London with a picturesque suburb. Both were in deep sympathy with movements to create a taste for artistic work among the people, and thought they saw an opportunity of introducing occupations which might be at once elevating and profitable to those round them. So Mr. Witter began to teach metal work to a couple of village boys, while Mrs Witter began to train eight little girls who came twice a week to learn art needlework. At first, and for some years, the workroom was the living room in the old-fashioned cottage in which these idealists were living, and as their school grew larger, the children had to come in relays, commencing in the early hours of the morning and going on throughout the day and well into the evening. What with the materials for work, the embroidery frames, and other appliances, it may readily be imagined that the accommodation was somewhat congested, and the time came when Mr. and Mrs. Witter found it necessary to hire a piece of ground at the end of their garden and build the workshop in which the exhibition was held last weekend.

Mrs Witter’s eight little girls have increased to sixty, and they are of ages varying from fourteen to young womanhood, some of them having been with her during the past ten years. They come as children, after they have left school, and we gather that it is the custom to make them a small payment from the first, the rate of pay increasing with their proficiency. The girls earn from 4s to 14s a week, and the lads can earn up to 19s a week, which cannot but be regarded as very satisfactory in a rural village, where the workers are living at their parents’ homes. Indeed, it is hinted that they might earn even more but for the modesty of their wants and the satisfaction that comes from pride in the beautiful work in which they are engaged. So successful is the School of Industries, and so considerable the demand for its output, that employment could be found for more trained girls and a few more beginners. By those competent to judge, the work is pronounced excellent. No doubt much is due to Mr. Witter’s artistic designing, but there are also adaptations and reproductions of any antique objects ofart. The great achievement on which Mr. and Mrs Witter are to be congratulated is their success in education, in the true sense of the term, the artistic faculty of the children of agricultural labourers and local workmen. Last winter for the first time, evening classes in drawing, etc., at this institution, were helped by the Herts. County Council, but apart from that the Ickleford School of Industries is absolutely and entirely the creation of private effort and enterprise.

A few words about the exhibition. The metal work is done in copper, brass, pewter, and iron (with often a mixture of metals which has a pleasing effect), and there is a certain amount of garnishing with stones and mother-of-pearl. The forge and anvil are used for wrought ironwork, but the appliances are now extensive or expensive. The designs are worked out, for the most part, in repoussé, and there were exhibited a great number of beautiful jugs and flagons and such articles as ink-pots, blotter-covers, tea-caddies, photo frames, candlesticks, a shaving-box, breakfast stand, name-plates for doors, letter boxes, knockers for both front-doors and bedroom doors, lamp brackets, electric light fittings, rose bowls, flower vases, and plaques beautifully designed, one giving a splendid presentment of the Royal Arms. All these objects had the appearance of solid worth both in design and workmanship, as Mr. Witter makes a study of the chief art collections, and no doubt carefully selects his designs. Some of the work is very massive. For example, there is a very noble mantelpiece in brass and steel. Mr. Witter is an authority on Church ornament, and in both metal and needlework there are some beautiful objects for ecclesiastical use. An altar cloth, with raised points and inlaid with mother-of-pearl, is much in demand.

The needlework is very various, but several of the examples shown were heirlooms and treasures which had been sent to the School for repair. One of these was a magnificent hand-woven piece of tapestry. The old flags of Chelsea Hospital have been entrusted to this School for the same purpose, and a quilt came from the Duchess of Rutland. We can only briefly note that we saw, as representing the work of the School, delightful specimens of tent or cross stitch embroidery for the seats and backs of chairs; a good deal of applique work for book and blotter covers, tambour work and Florentine embroidery, richly embroidered curtains, four pairs of which have been made to order, chalice veil, altar cloths and stoles, most beautifully designed and finished; a quaint bed quilt copied from one made in the reign of Charles II, for the bed of the French Ambassador at his visit for the ratification of peace, part of the design showing the dove bearing the olive leaf; table centre from a Tudor pattern, some delightful tent stitch work in silk, and others too numerous to specify. Of piquant interest were the unique specimens of “stump” work of the Stuart period, sent to the School to be restored. The figures in this form of ornamentation are padded out into relief and dressed like little dolls, and the panels depict scriptural subjects, such as Abraham about to sacrifice his son, Rebekah at the well, and the little figures, even to the camels and the fig trees and the angel in the clouds, are most quaintly represented. The work of copying or restoring these figures is one of great delicacy and skill.

A certain amount of leather work is successfully done. This takes the form of covers for pocket books, golf scoring books, blotters and purses. Noteworthy, too, is the handsome screen of lacquer leather work in the old Spanish and Italian style.”1

Walter Witter was born on April 10th 1863 in Cheshire. He and his elder brother Arthur, were involved in the building enterprises of their father, William Preston Witter, during their youth, but both were more interested in drawing and painting in their free time and they would often skip work to go to the nearby woods to paint. Arthur Witter actually had some of his works exhibited at the Royal Academy, Liverpool and in other exhibitions between 1882 and 1904.

Walter met Marian Gaskell, who was also from Birkenhead, Cheshire. Her father was a cotton broker: her mother came from a large, talented family, many of whom made their names in the arts, literature, legal and stage professions. Her uncle, Jonathan Carr, acquired land at Turnham Green railway station in London and developed the renowned residential area of Bedford Park there. Jonathan Carr also built a School of Art, which became known as the Chiswick School of Art. The art school, together with a community clubhouse, helped to establish the reputation enjoyed by Bedford Park at the height of its popularity and many leading artistic and literary figures of the day used to live and visit there. The School of Art opened in 1881 with the aim to offer courses in “…freehand drawing in all its branches, practical geometry and perspective, pottery and tile painting, design for decorative purposesas in furniture, metalwork, stained glass…”. This is where Walter trained as a teacher of Arts and Crafts.

On January 4th, 1900, Walter and Marian (Marie) married and went to lodge in Freewaters Cottage in Ickleford, Herts. Walter took up a teaching post in Hitchin – probably at the Literary and Mechanics Institute whilst Marie, who was an expert needlewoman, carried out orders for embroidered trousseaux. She began teaching embroidery and needlework to the village schoolgirls at weekends and during holidays. As the girls left school they went to work full time with Marie. During this time Walter interested local boys in the art of making beaten brass and copper work. Their son Carr was born in 1902 and gradually the cottage began to bulge with school-leavers, needlecraft and metalwork so, in 1904, a workroom was put up in the meadow beside the cottage to house the 25-30 men and women employed in the business. A second building was added in 1906 to create a workshop for the brass and copper work and a forge for the wrought iron. The tapestry workroom was built with a platform at one end dressed with large curtains. Examples of the tapestry work was hung on the wall of the workroom.2

It seems that metalworking started almost immediately after the couple moved to Ickleford. The first mention of metalwork being exhibited was in June of 1900. The Queen newspaper illustrated a few items made by the class that had been displayed at the Home Arts and Industries Association exhibition which had been held in May at the Royal Albert Hall in London.3

The Queen, June 1900

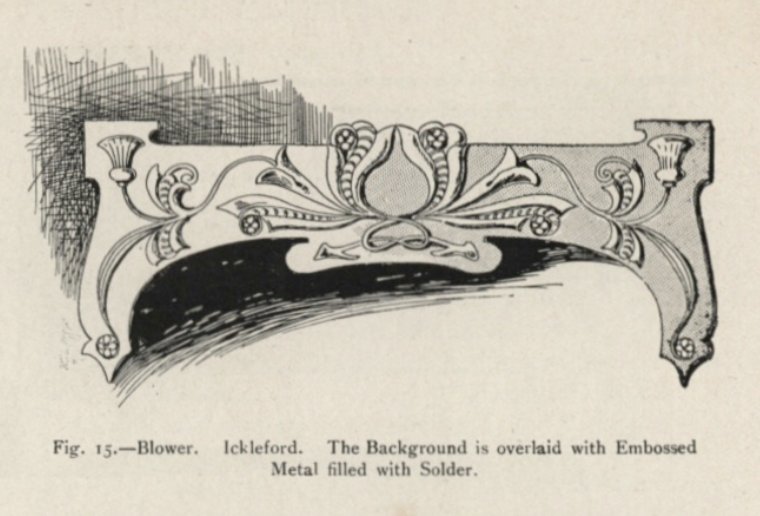

In July of 1900 The House periodical wrote a review of the same Home Arts and Industries Association exhibition. The Ickleford class gets a special mention; “The Ickleford and Wymondley display included many ambitious pieces, well executed and embodying very ingenious ideas. The metal work was largely in copper, but overlaid in many cases with brass. In the illustration (Fig. 15), for instance, the blower is first of all constructed in copper, the repoussé is then made in brass, cut out, filled with solder until it forms a solid mass, and then imposed upon the copper foundation. A screen was also done in this way, and although the pieces so constructed are rather heavy, there is no doubt about the ingenuity, and, in many cases, effectiveness of the method.”4

Blower illustrated in The House, July 1900

The next mention of metalwork being displayed was at the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society exhibition in August of 1900. It was turning into a great year with the Ickleford Class being awarded a first silver medal ahead of the Newlyn and Yattendon classes. Walter Witter is clearly called out as the designer.5

In 1901 the class was again exhibiting metalwork at the Home Arts and Industries Association exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall in London.6 Later that year the class exhibited both leather-work and metalwork at a Home Arts and Industries exhibition in Cheltenham. Their work was specifically mentioned in reviews of the event; “From Ickleford, Hertfordshire, came another collection of metalwork which in boldness and breadth of design and strength of execution, was quite unique. A casket of combined copper repousse and leather worknad a most artistic fireplace were two of the best exhibits on this attractive stall”.7 An R. Raven from Ickleford won a second prize in the Metal Repousse (Pewter) category. Walter Witter won a first prize in the copper category notably beating John Williams or the Fivemiletown Class into second place.7

In 1902 the class was again mentioned by The House periodical in their review of the annual Home Arts and Industries Association exhibition; “Metal, Leather and Needlework were shown. The needlework included a portiere embroidered in brown and gold on a green satin ground. The metalwork included a copper fire-screen, canopy and fender of very bold and striking work. A pewter repousse cover for a blotter and an ornament for a table centre were among many other interesting features.”8

In 1903 the Class exhibited at the Industrial Art and Loan exhibition in Gloucester and an Arts and Crafts exhibition at Newbury.9,10 In 1904, Walter and the Class won a number of prizes at the Royal Cornwall Polytechnic Society exhibition. In 1906 at the Hertfordshire Arts Society exhibition in Berkhampstead the class won first prize in the Hammered Iron category and a first prize in the Repousse Brass and Copper category. Interestingly the completion judge was W.A.S. Benson.11

The class continued to exhibit their work over the next several years with exhibitions in Codicote, Hertford, Cheltenham, Lewes, Luton. They are mentioned again in 1908 in relation to the annual Home Arts and Industries Association exhibition where they exhibited a repousse brass altar cross decorated with mother of pearl. 12

In 1913 the class features in an article by the Queen newspaper on visits to industrial art schools in rural England; “Our people are artistic. Our boys and girls can go anywhere and do anything, affirms Mr. Witter, who with his wife, founded some thirteen years ago in a village the Ickleford Industries of Applied Arts, which now employs ninety young people gathered from the families of labourers on the land, small tradesmen, &c. The boys are taught to work in wood, metal and leather. The girls have sufficiently mastered all the intricacies of embroidery, tapestry making, and renovating to be entrusted with the execution of a magnificent specimen of heraldic work in the manner of a firescreen for Sir Ernest Cassell. They have also reason to be proud of having repaired with entire satisfaction the war worn flags from Chelsea Hospital”.13

Walter Witter left his teaching post in Hitchin sometime between 1904 and 1908 to concentrate on the business full time. Some of his first students included Francis Olney and Tom Newbury, aged 13. They were employed in 1906, to learn forging skills and the business known as “The Ickleford Industries of Applied Art” was inaugurated. In 1911 Arthur Witter went to live in Hitchin and joined his brother in the growing business making Art & Crafts copperware, pewter ware and wrought iron work. With the outbreak of the First World War, however, the company dwindled as the young men went away to fight in the war. During this time, Walter Witter made aeroplane propellers in Ipswich alongside Frederick Tibbenham (manufacturer of reproduction furniture).2

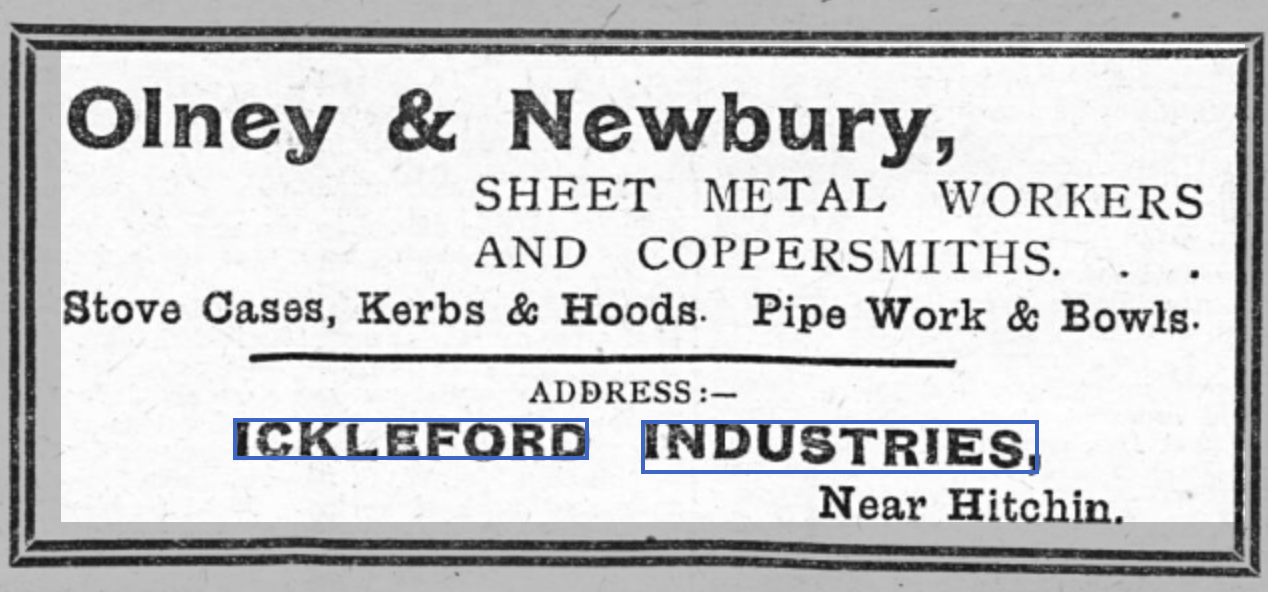

After 1916 embroidery, needlework and metal work continued to be carried on in Ickleford for a while under the direction of Mr. Witter’s personal assistant, Madeleine Warren, but in 1923 the forging and metalwork side was handed over to Francis Olney and Tom Newbury, two of the earliest pupils at “The Ickleford Industries of Applied Arts”. They renamed the firm “Olney and Newbury Ltd” with a trademark ‘Hand Beaten, Olbury, English Made’ Olbury being a contraction of Olney and Newbury.2

Newpaper advertisement, 1919

Much more information can be found on the following excellent websites:

https://www.hitchinhistoricals.org.uk/history-of-hitchin/ickleford-applied-art-industries/

http://www.thewittercollection.co.uk

1 – Bedfordshire Times and Independent – Friday 24 June 1910

2 – Hitchin Historical Society article on the Ickleford Applied Art Industries

3 – The Queen, June 1900.

4 – The House, 1900, No 41 p.166

5 – Cornish Echo and Falmouth & Penryn Times – Friday 24 August 1900

6 – Gentlewoman – Saturday 25 May 1901

7 – Cheltenham Chronicle – Saturday 30th November 1901

8 – The House, 1902, No.65, p.180

9 – Gloucester Journal – Saturday 28 March 1903

10 – Reading Mercury – Saturday 02 May 1903

11 – Herts Advertiser – Saturday 16 June 1906

12 – Morning Post – Thursday 18 June 1908

13 – The Queen – Saturday 15 November 1913