Alfred Hughes - Forgotten Master Craftsman

Although this story is primarily about a forgotten art metalworker, Alfred Hughes, it really has to begin with Richard Llewellyn Rathbone (1864-1939). Rathbone was a designer and metalworker of great renown. His father was a Liverpool merchant but the family had excellent connections into the Arts and Crafts Movement. One cousin was Harold Rathbone, Head of the Della Robbia Pottery, and another cousin was William Arthur Smith Benson who ran a successful Arts and Crafts metalworking business. In fact, Rathbone is believed to have trained with Benson at his firm in London before establishing his own metal works. Rathbone is also known to have produced metal fixtures and fittings for many well known Arts and Crafts architects and designers including Arthur H. Mackmurdo, Heywood Sumner and C.F.A. Voysey.

Alfred Hughes had much a humbler beginning. He was born in 1855 in Birmingham and was the son of a gun maker. In 1881, at the age of 26 he was listed as a Brass Fitter and by 1891, still based in Birmingham, he was listed as a Metal Caster.

The earliest mention of Alfred Hughes in connection with Rathbone is in 1889 and it is clear that Alfred’s metalworking skills were already well developed. At the 1889 Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society exhibition, Rathbone exhibited a pendant for three incandescent electric lamps and three incandescent gas lamps. They are described as “Designed by Richard Rathbone. Brass-work by Robert Simmonds and Alfred Hughes.” The collaboration continued in 1893 when Alfred Hughes was listed as making a brass sanctuary light and a cast gun metal altar cross designed by R. LL. Rathbone and exhibited at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society exhibition. The pieces exhibited this year were made in conjunction with Cox Sons/Buckley & Co, and were allegedly designs for, or by, MackMurdo.

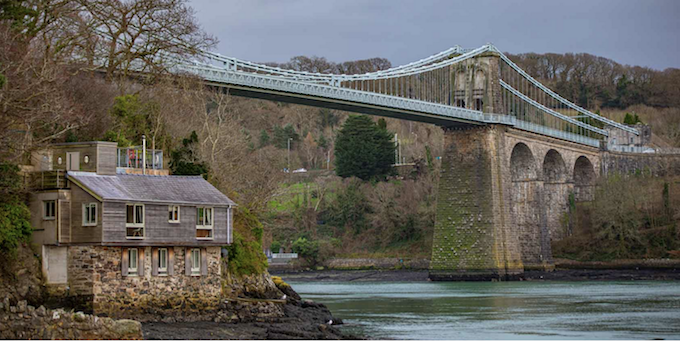

Rathbone exhibits an increasing amount of metalwork at the Society’s exhibition in 1896. In total, nine pieces were exhibited. Alfred made two exhibits and one was made by H. P. Hall, with the others presumably being made by Rathbone himself. The addresses for the two men shown in the catalogue suggest they were now working together at Rathbones new workshop close to the Menai Bridge in north wales:

– R. LI. B., Manadwyn, Menai Bridge, North Wales.

– Hughes, Alfred, 3, Fairview Terrace, Menai Bridge, North Wales.

Manadwyn next to the Menai Bridge

Manadwyn was purchased by the Rathbone family in the late 19th Century and Rathbone used the house as his workshop and studio. It seems highly likely that Alfred was working full time for Rathbone in the workshop.

By 1901 a 45 year old Alfred is living at 90 Northumberland Terrace in Everton. He is listed as a Foreman, Metalworker in brass, copper, silver and iron. His 20 year daughter, Emily, and his 19 year old son, Charles, are also both listed as metalworkers. It is highly likely that all three were working at Rathbones’ workshop that was based at Everton in Lancashire. Rathbone was literally living just down the road at number 37 Northumberland Terrace in Everton and notably sharing a house with the designer and metal worker, Harold Stabler. Stabler had been manager at the Keswick School of Industrial Arts between 1898 and 1900.

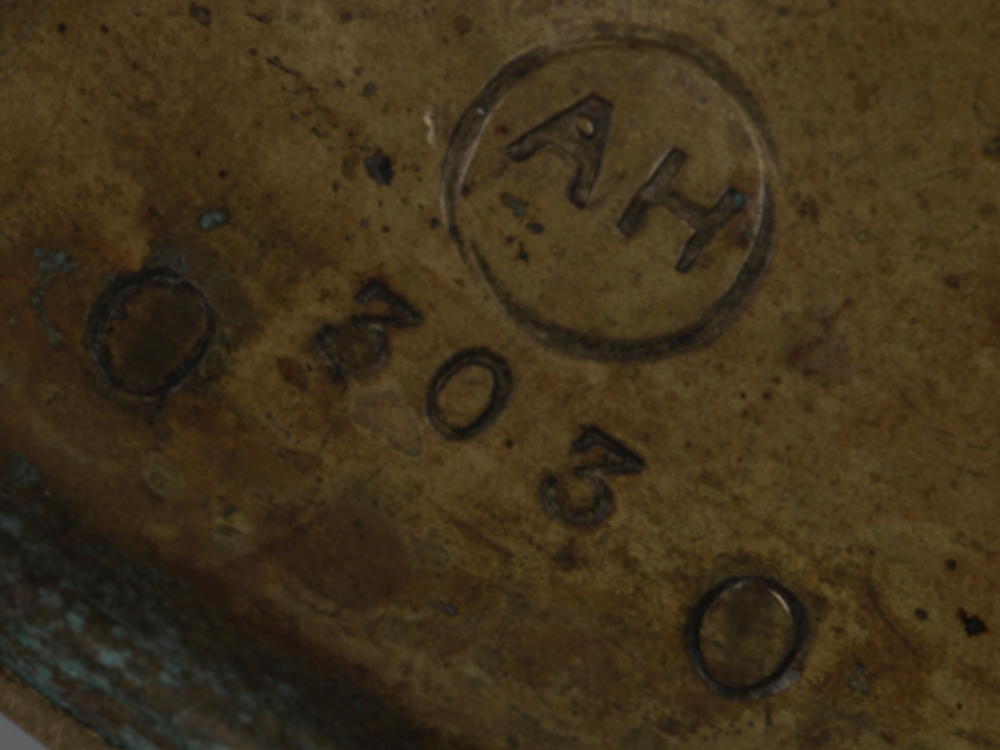

The 1903 Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society exhibition appears to have been the peak of Rathbone’s output as a metalworker with a large display of metalwork under the name of R. LL. B. Rathbone & Co. He exhibits no less than 20 items. Alfred is involved in the making of fifteen of these items. His son, Charles, is also involved in the making of 4 of the items alongside his father. On the box of a copper casket from 1903 the makers’ marks for both Rathbone and Alfred Hughes are both evident.

Makers marks on the underside of a 1903 copper box

It is notable that Harold Stabler also appears to be collaborating with, or working for, Rathbone. In the 1903 exhibition he is both designing and making several exhibits alongside Rathbone. At least four items exhibited by Stabler were made by Alfred or Alfred and Charles together.

Rathbone appears to have been teaching at a metalwork class in Liverpool University around the period 1898 to 1903. He may well have met Harold Stabler at the university as he is known to have attended the art department there after his apprenticeship as a wood carver in Kendal.

Around 1902, Rathbone sells many of his lighting, door furniture and inkwell designs to the Faulkner Bronze Company. By February 1902, advertising that The Faulkner Bronze Company of Milton Works, Tenby Street, Birmingham, had purchased all the designs, drawings and templates relating to his cabinet handles and hinges. At least two light fittings and the copper colouring processes.

It appears that Rathbone’s thoughts turned more towards teaching as time went by and around 1905 he moved to London to take up the post of Head of the Art School of the Sir John Cass Institute. He also taught at the LCC Central School of Arts and Crafts. He worked mostly in base metals, but also made a certain number of pieces of jewellery, some of which were shown at the Arts and Crafts Society exhibition in 1906.

The 1906 Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society exhibition marked a pivotal point for Alfred Hughes and Rathbone. Rathbone was by now a member of the Society and also a member of the selection and hanging committee. He exhibited numerous articles of jewellery and metalwork under the banner of the Sir John Cass Institute. Both Harold Stabler and Alfred Hughes are also named in the listing of the metalwork exhibits suggesting the collaboration had continued and all three men were now in London and associated with the Institute.

Interestingly, both Harold Stabler and Alfred Hughes both exhibited items in their own right. Alfred exhibited an inkpot in beaten copper, a candlestick in beaten brass a beaten copper box and silver jewellery. His son Charles Hughes also exhibited metalwork and an Arthur Hughes, almost certainly Alfred’s son called Arthur, made one of Alfred’s designs. Metalworking skills clearly ran in the family.

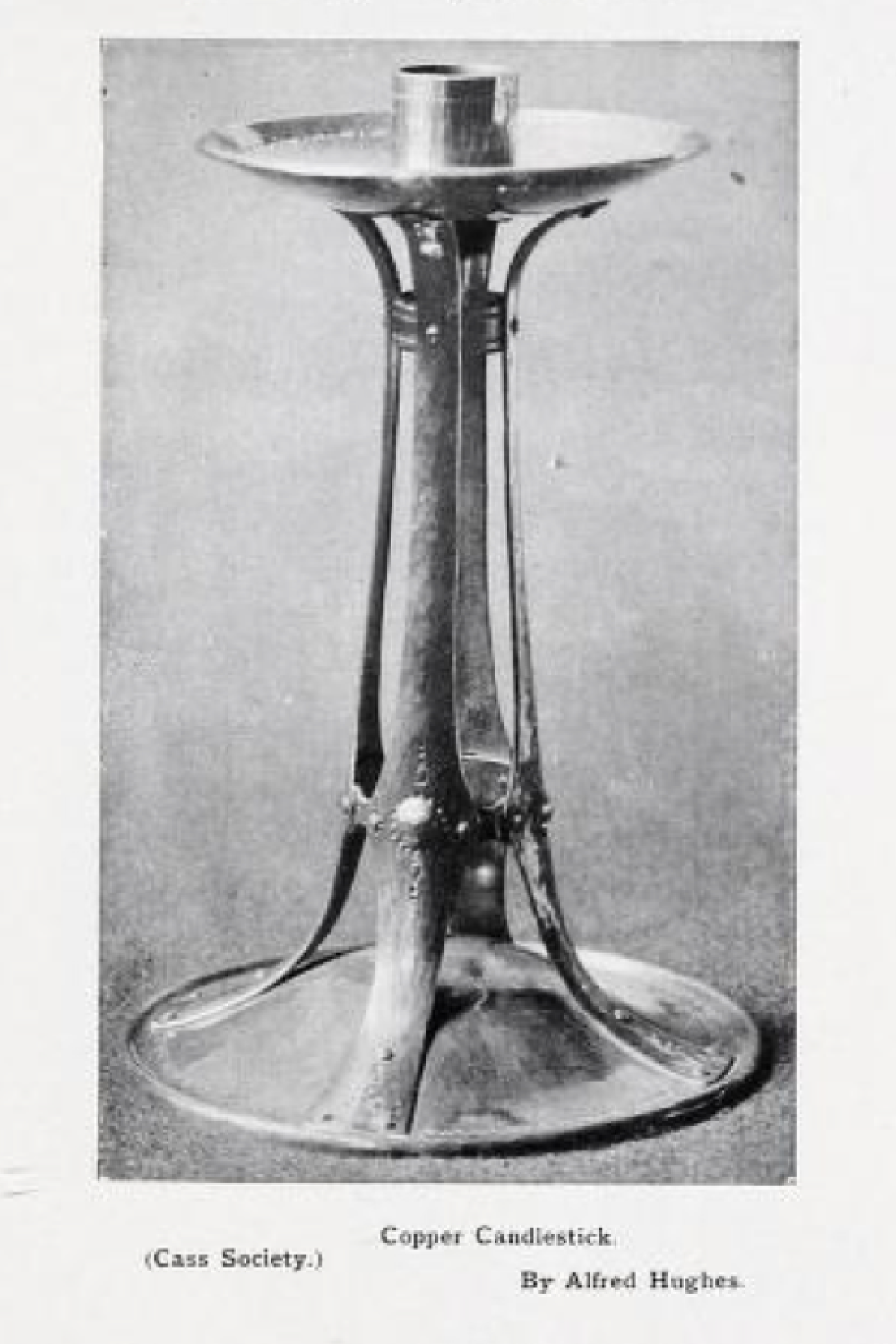

In 1906 The Art Journal covered an exhibition held by the Sir John Cass Institute. Alfred contributed as an honorary member to the exhibition:

“The metal-work of the Institute, which was mainly represented by the productions of present students, is equally a development of teaching that bases design on appreciation of processes of formation. Shape and ornament represent technical exercises in the material and in the use of tools directed to the expression of the artistic value of the process, The candlesticks of Mr Alfred Hughes, who contributed as honorary member to this part of the Exhibition, demonstrate in practice the possibilities of simple construction, so illustrating the principles which control the students’ work.”

Candlestick exhibited by Alfred Hughes at the Sir John Cass Institute exhibition in 1906

It was this candlestick that brought Alfred to my attention. In March of 2019, the auction house, Toovey’s, sold a pair of brass candlesticks to the same design. Thankfully the candlesticks were marked with Alfred’s makers mark. Safe to say I wasn’t successful in my bid!

Image from Toovey’s auction sale, March 2019

Image from Toovey’s auction sale, March 2019

In fact Alfred was teaching metal work in the Arts and Crafts department at the Sir John Cass Institute where Harold Stabler was the Head of the Department.

Ilford Recorder, 15th Sep 1905

Fast forward to 2022 and out of the blue I am asked a question about a copper candlestick coming up for auction in the United States. It had the same makers mark! With a huge amount of assistance from Bryan Mead at HammeredHewn I was able to successfully repatriate the candlestick to the United Kingdom. The story of how it ended up in the United States we will never know.

Several images of the candlestick are shown below. I’ve seen a lot of Arts and Crafts metalwork in my time but my heart skipped a beat when I first saw and held this piece. It is beautifully designed with perfect proportions and a lovely weight. Every inch is delicately hand planished and the organic curves and design details are quite astonishing. Finally, the riveted construction throughout illustrates the continued impact of Rathbone’s designs on his own work. The condition and patina suggests that this piece has been both loved and understood for a long time. I’m very pleased to have acquired this piece and given it back a little bit of it’s history. I will be holding on to this for a while.